Better Places

更好的地方

2024

"You are going to a better place!"I often heared them say this.

你就要去更好的地方了!我經常聽到他們這樣說

Series

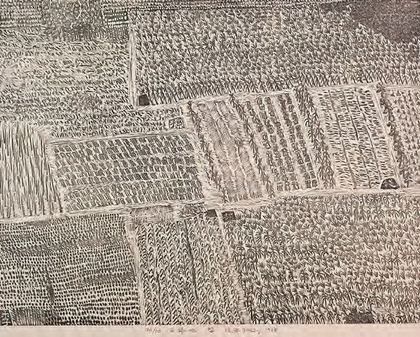

Adapter II

變壓器之二

marker on paper

丙烯麥克筆、畫布

Annotated bibliography

Since moving to Melbourne, my work has centred around themes of migration, identity, memory, and belonging, reflecting the experience of living between multiple cultures.

In my Better Places series, I focus on the internal spaces of homes and the trajectories of daily life, with floor plans serving as the main visual structure.

My mapping works embrace the postmodernist concepts of uncertainty, fragmentation, and multiple perspectives. By using distortion and displacement, I challenge the objectivity of traditional maps, revealing how memory, personal experiences, and individual viewpoints reshape our understanding of space.

“The one who draws the map holds the power of discourse.” Floor plans and maps, as reference texts for real spaces, are often regarded as precise, rational, and objective. However, this is not the case. When we look at a map, we see the world from the perspective of the person who created it, and this act carries strong political implications and personal viewpoints. Every map has a subjective backstory, and every mapmaker is a storyteller. This phenomenon can be observed in the works of Tennant Creek Brio, Senoh Kappa, Qiu Zhijie, and Emma Kay.

The timeline and trajectory are also key themes in this list.

When space remains fixed, the flow of time within it becomes the primary subject of observation. In Peter Dreher’s work, the gradual withering of flowers speaks to the passage of time.

In Vilhelm Hammershøi’s paintings, there are frequent depictions of interior spaces, light, furnishings, and his wife. In Not Under My Roof (1), stains and grease marks on the carpets in each room form distinct trajectories. These traces of life serve as subtle yet powerful hints, evoking the essence of home.

Nietzsche’s theory of Eternal Return suggests that all of our actions will be repeated infinitely over time. From this perspective, the repetitive behaviours in daily life, such as eating, walking, and tidying up, construct not only our everyday rhythms but also gradually shape a sense of belonging and the meaning of home within a space. These repeated actions function like an invisible ritual, allowing us to find inner stability through the process of becoming familiar and re-familiarising ourselves. Through repetition, our perception of space is reinforced, and home becomes more than just a physical environment; it transforms into a psychological place built from actions and memories.

(1) Claire Healy and Sean Cordeiro. Not Under My Roof. Contemporary Australia: Optimism, curated by Julie Ewington. Installation. Found flooring from farm house (wood, linoleum). Accessed August 31, 2024. https://claireandsean.com/large-scale-projects/not-under-my-roof.

Tennant Creek Brio: Juparnta Ngattu Minjinypa Iconocrisis

Tennant Creek Brio. (2017-2024). Tennant Creek Brio: Juparnta Ngattu Minjinypa Iconocrisis [Exhibition]. Melbourne, Australia: ACCA. 21 Sep 24 – 17 Nov 24.

https://acca.melbourne/exhibition/tennant-creek-brio/

This exhibition addresses the historical theft of Indigenous lands, which have suffered from mining activities and nuclear pollution. The artists have overlaid Indigenous cultural patterns and thought-provoking slogans onto old factory maps and river topographies. Even without reading the content, simply stepping into the exhibition space and seeing walls covered with red paintings—like splattered blood—is already overwhelming. "Overlaying" is a powerful act, symbolising correction or reclamation. The application of emotionally charged colours and brushstrokes over the calm, industrial lines is undoubtedly a form of protest against these factories.

Although my way of working is quite different from this piece (appearing much cleaner in comparison), alteration and overlay are the common threads between us.

Peter Dreher:

Day by Day good Day

The Clover Flower

Labour and repetition have always been topics of great interest to me, and these two aspects are fully realised in Peter Dreher's work. In Day by Day Good Day, the artist repeatedly paints the same glass, requiring himself to complete each painting within a single day, much like a diary. Meanwhile, The Clover Flower depicts a clover gradually withering inside the glass.

Although the images are still, time becomes the central theme running through the entire series. The glass, when viewed in isolation, carries little meaning—just an everyday object. However, the real focus of the work lies in the time and effort the artist invested throughout the series.

Vilhelm Hammershøi

I greatly enjoy viewing Vilhelm Hammershøi’s works. He depicted many interiors of homes and his wife, creating paintings filled with a serene domestic atmosphere yet tinged with a sense of mystery. The light from windows and half-opened doors seem to lead into another imagined space, and his wife’s posture reminds me of figures from Magritte’s portraits—elegant yet uncanny. As a viewer, I feel like an intruder who has suddenly barged into his quiet home. However, there is nothing to steal here—only empty, orderly rooms that compel me to reflect on the meanings of homely and unhomely.

The Architectural Uncanny :

Essays in the Modern Unhomely

Vidler uses the concept of the uncanny, as developed by Freud, to explore representations of estrangement in architecture. He argues that the uncanny is not inherent to spaces but is a cultural sign of estrangement that varies across historical and cultural contexts.

In my work, the sense of estrangement from one’s living space is a significant element. The book explores the essence and symbols of "home," as well as how familiar environments can become alienating and induce anxiety due to minor changes.

Senoh Kappa:

Big difference in working places

Big difference in toilets

Senoh Kappa visited the workspaces of many famous Japanese figures, including renowned writer Kawabata Yasunari and fashion designer Issey Miyake. Kappa used a bird’s-eye perspective to illustrate the interiors of their studios, capturing the entire space. In the accompanying text, he recorded detailed descriptions of the rooms and the interview processes. Each chapter combines images and words to vividly present the working habits and personalities of the space's owners.

I am very interested in this way of presenting living spaces as if they were part of a catalogue. I also view my own work as a kind of catalogue, although mine resembles specimens more than a catalogue—they lack a sense of life and appear almost dead. Like Kappa, I have also started adding textual descriptions to accompany my works.

Clarice Beckett was a key member of the Australian tonalist movement, known for her subtle, misty landscapes of Melbourne and its suburbs.

After completing the floor plan, I began shifting toward oil paintings related to scenes from that living environment. The scenes from my memory have faded and blurred over time, with the images and tones becoming indistinct. Most of the time, the scenery seems to merge with the surrounding air. Clarice Beckett’s palette has been a great source of inspiration for me, and the living environments she depicted have also deeply influenced my work.

Canadian photographer Christopher Herwig travels former Soviet Republics from Ukraine to Uzbekistan, Armenia to Far Eastern Siberia, and all points in between, in a decades-long bus stop treasure hunt across more than 50,000 kilometres.

I have always been fond of Soviet-era architecture—its geometric shapes, coldness, sharpness, and use of concrete and steel, which stand in stark contrast to the comfort and warmth emphasized in contemporary architecture. These buildings, designed as bus stops, only needed to provide basic shelter from the sun and rain while people waited (and some didn’t even fulfil that function). Since people wouldn’t stay in these spaces for long, domestic elements were greatly omitted. These bus stops, with their strange forms, stand tall across vast landscapes. Whether still in use or abandoned, they remain unaffected by time, people, or even changes in regimes—they are merely witnesses to passing events.

Xu Bing: Landscript

At the heart of Xu Bing’s art lies the theme of language. In Chinese art, characters hold deep symbolic significance. Xu Bing’s Landscript series integrates this by using Chinese characters to represent various elements of nature within landscape paintings. For example, the character for "stone" forms images of rocks, "tree" shapes trees, and "grass" represents grass. Through this approach, Xu Bing transforms language into a visual medium, bridging the gap between text and imagery.

Xu Bing's work makes me feel the power of language and symbols. It reflects the dislocation of memory and space, showing that language is not merely a tool for communication but a way to reshape our understanding of the world.

Healy, C., & Cordeiro, S. Not Under My Roof.

Contemporary Australia: Optimism [Installation].

Found flooring from farmhouse (wood, linoleum).

https://claireandsean.com/large-scale-projects/not-under-my-roof.

In this work, the artist removed the floor of a farmhouse and installed it on the exhibition wall, creating a "living" 1:1 floor plan. To me, this work resembles a specimen rather than a floor plan, as the oil stains and dirt on the carpet reveal traces of the house's "life."

When I create works related to floor plans, I often lose a sense of personal identity. I've always struggled with how to incorporate an inbody experience while preserving the cold and uncanny feeling of architecture, and Not Under My Roof has provided me with a new direction for exploration.

Qiu Zhijie:

Map of Technological Ethics

2018

Qiu Zhijie’s large wall painting Map of Technological Ethics (2018) presents an archipelago of moral dilemmas in applied science. Its islands and landmarks are named after activists, political groups, medical and biological controversies, and fears surrounding technocracy and climate change.

In Qiu Zhijie's work, I feel how visual symbols can convey complex concepts—giving form to seemingly abstract ideas in space. This resonates with my approach of exploring memory and space through maps and objects.